Aleksandra Aleksandrovna Exster

b. Białystok, Poland, 1882–1949

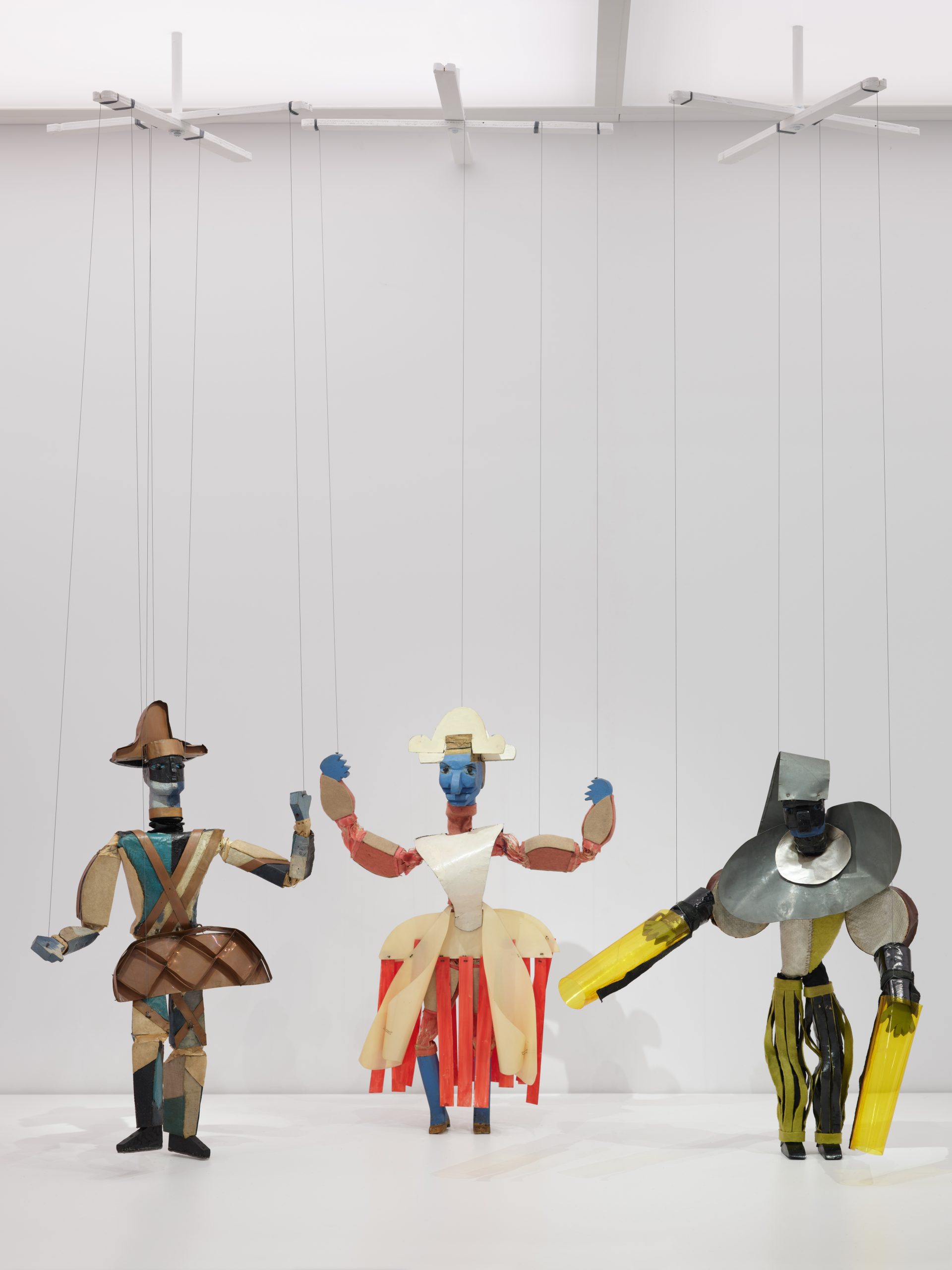

Marionettes

1926

Wood, paint, metal, tin, fabric, thread, and plastic

Gift of Joseph H. Hirshhorn, 1977 (77.22)

About Museums Without Men

Celebrated art historian Katy Hessel has launched an audio guide series highlighting the women and gender-nonconforming artists in the public collections of international museums. Museums Without Men is an ever-growing series that introduces museum visitors to underrepresented and often lesser-known artists, opening up collections to new and existing audiences who will be able to follow the audio stops while in the galleries or online. The series links public institutions globally, including the Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco; the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York; the Hepworth Wakefield, UK; the Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden, Washington, DC; and Tate Britain, London, to foreground the important work that museums and galleries do by collecting and displaying women and gender-nonconforming artists, whether historical or contemporary.

Transcript

[00:00:00] Aleksandra Exster, Marionettes (1926). Aleksandra Exster, born in 1882, is known as one of the Amazons of Russian art, a group of women artists working at the start of the 20th Century, whose dynamic style mirrored the speed of industrialism and who became extremely successful. But, after the Russian Revolution of 1917, Exster joined the Constructivists, artists whose works comprised angular lines and geometric shapes executed in bright, bold color.

You can see the influence of the Constructivists in the sharp angles of this marionette from 1926. Because this is also when she began applying her style to stage design. In the early 1900s, Europe was a [00:01:00] haven for artists breaking out of their art forms, melding graphics, sculpture, textile and fashion.

Theater directors often collaborated with artists on their productions, and Exster was celebrated for her stage designs as well as costumes for the film Aelita in 1924. But here we see her marionettes, puppet like figures she configured from painted wood, copper and steel. She enhanced their kinetic experience by using balls and textile links to make them as flexible and multitudinous as possible.

Professional puppet theater was a popular art form in Russia. As puppeteer Nina Simonovich-Efimova once said, “the puppet’s charm lies in movement. The meaning of their existence lies in play.” And it’s this notion of play that attracts artists like [00:02:00] Exster to the art form. Puppeteering can encompass literature and the visual arts, and I love how, through this medium, you can create a character, tell a story, and actually bring art to life: from designing costumes, hats or masks; experimenting with the many directions their angular limbs can move in; and the personalities and professions you can project onto them. Exster’s characters range from harlequins to policemen, and what I love most is how they tie in with a constructivist painting, as though they are living embodiments with their angular lines, bold coloring, sharp features, and holding many possibilities for a new, post revolution, utopian world.