Strange Bodies: Figurative Works from the Hirshhorn Collection

Dec 11, 2008–Nov 15, 2009

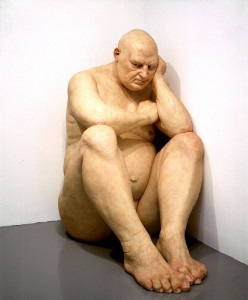

Ron Mueck, Untitled (Big Man), 2000. Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, DC, Museum Purchase with Funds Provided by the Joseph H. Hirshhorn Bequest and in Honor of Robert Lehrman, Chairman of the Board of Trustees, 1997–2004, for his extraordinary leadership and unstinting service to the Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden

December 11, 2008, to November 15, 2009

An important strength of the Hirshhorn is its holdings in figurative art, and Strange Bodies brought together some of the most praised and popular examples from the collection. Works on paper can be on view for only several months at a time in order to maintain their best condition, and exhibition curator Kristen Hileman took this opportunity to introduce diverse pieces into the mix. Works that had not been on view for some time; new acquisitions, such as Yinka Shonibare’s The Age of Enlightenment—Antoine Lavoisier (2008), a then-recent purchase; and a few surprises were switched out for some of the more delicate works.

Mid-July was viewers’ last chance to see the Hirshhorn’s unique in-depth collection of works by George Grosz, which were replaced by the poetic yet unsettling film A Life of Errors (2006). Made by the young Canadian artists and husband-and-wife collaborators Nicholas and Sheila Pye, the piece was acquired through the Hirshhorn’s Contemporary Acquisitions Council in 2007.

Looking back to works from a slightly earlier era, other newer additions to the show included James Rosenquist’s 1961 The Light That Won’t Fail I, a painting that presents fragments of the body in a fashion at once Pop and ethereal. Georg Baselitz’s Meissen Woodsmen, from the same decade, demonstrates a different approach to painting, fracturing figures to the point that they begin to disintegrate into abstraction.

The overall grouping of sculptures, paintings, drawings, and film that composed Strange Bodies spanned the past century, but the works revealed a common impulse toward depicting the human body, whether in a realistic, expressionistic, or surrealistic fashion. The loaded, at times dark, content that figurative art can carry was explored through the works on view, as was the fundamental human connection that occurs when one encounters an image of a fellow individual.