Focus on Conservation: Uncovering Robert Rauschenberg’s “Fossil for Bob Morris,” 1965

As part of its commitment to research, care for, and interpret art in the Hirshhorn collection, the Museum’s conservation department is undertaking in-depth studies of Robert Rauschenberg’s Fossil for Bob Morris (1965) and Dam (1959), supported by a generous Bank of America Art Conservation Project grant. Join us as we investigate these two masterworks and—through posts on both this page and social media—reveal what we are learning about how they were made and how they can be best conserved.

In the spirit of the artist’s own work, our endeavor is collaborative, and it draws on conservation expertise across disciplines and institutions. The project builds on both academic and scientific research as it engages with the works’ complex materials and history and the intriguing context of their creation to determine their conservation needs and to ensure that the works continue to convey Rauschenberg’s original creative vision. Our work will add to existing scholarship about the artist’s work as well as vital ongoing discussions about how to conserve complicated works of contemporary art—some of which are not made of traditional media such as paint and bronze, but instead of found objects, materials that degrade quickly (and sometimes intentionally), and even ephemeral materials such as water, sound, and air.

Fossil for Bob Morris was displayed in the Museum’s inaugural exhibition and has been a critical component of the collection ever since. It is also a quintessential example of Rauschenberg’s approach to art-making. To understand this work, like any other, conservators rely on a most basic tool: their eyes. Conservators use visual analysis both to understand which materials and techniques artists used to make their works and to evaluate those works’ condition. Close looking is sometimes coupled with scientific analysis to strengthen our knowledge of how materials in an artwork interact and degrade and to guide treatment decisions. Consulting historical images is another important tool, as it helps conservators discern how much an artwork has changed over time—something that is critical with a work such as Fossil, which comprises an array of found materials, all of them already in various states of decay at the time Rauschenberg made the artwork.

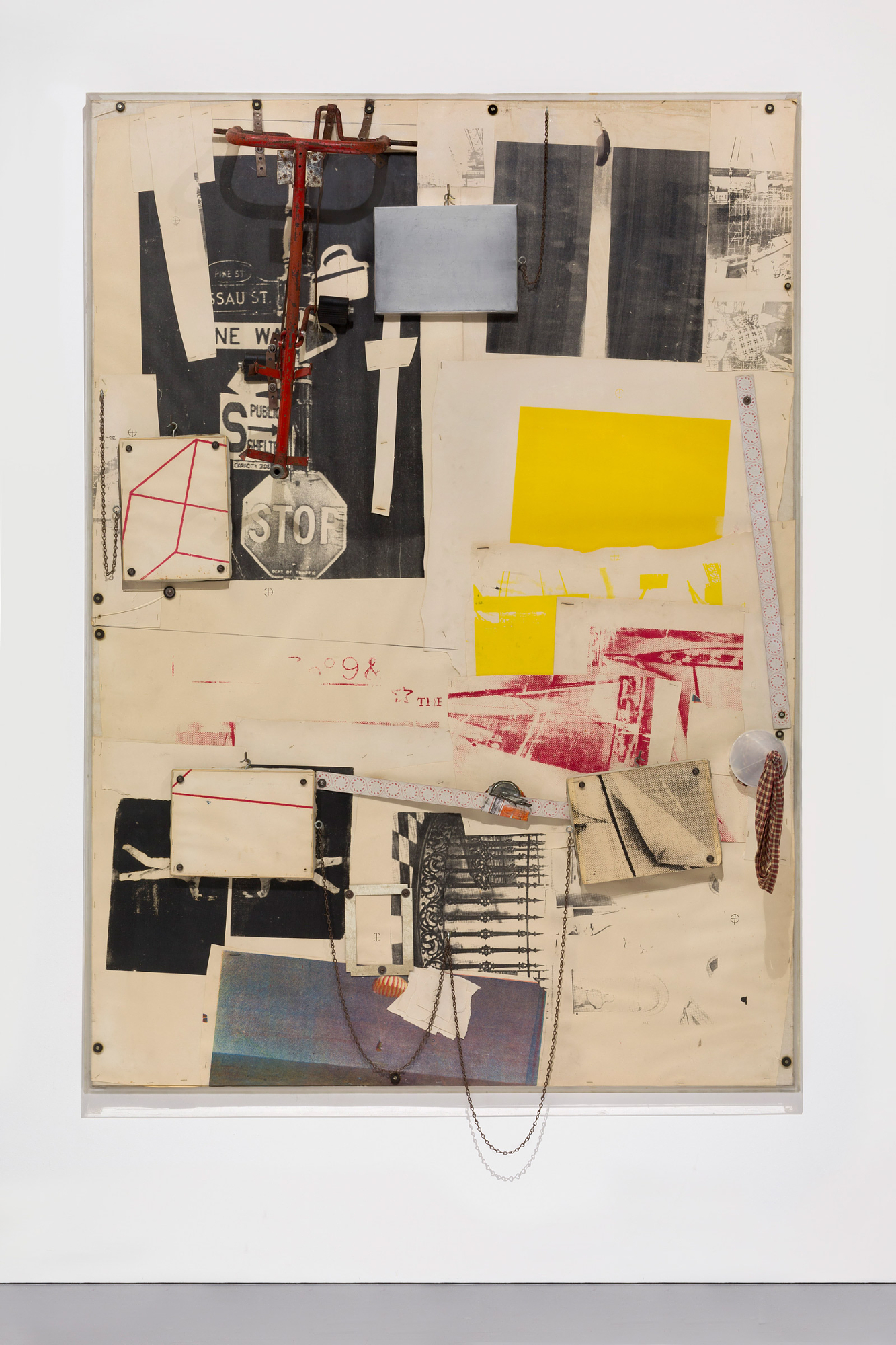

Although it was once classified as a painting due to its construction, there actually is no paint on Fossil. Instead it consists primarily of a prepared canvas stretched onto a wooden strainer, with cut and torn screenprints secured to the surface with metal, wires, staples, and occasionally adhesive. A clear acrylic sheet covers the surface and is attached to the edges of the wooden strainer with rubber gaskets used as washers and metal screws. Moveable constructed elements and reclaimed objects (such as a pedal bike frame and a plastic funnel) are secured to this main panel.

Our analysis and treatment of Fossil focused on restoring areas of the work that had changed over time due to incidental damage while preserving other areas that seemed damaged but were in fact artifacts of Rauschenberg’s art-making process. For example, a large crack in the acrylic sheet and corrosion of the pedal bike frame both can be spotted in historical images of the work. Thus these elements were not altered in conservation treatment.

However, conservation records indicated that the plastic funnel had been replaced at some point, resulting in an alteration of the architectural drape of the shirt fragment that extends from the funnel stem. Conservators stabilized the shirt fragment, replaced the funnel with one that more closely matched the original, and discreetly altered the funnel to enable reconfiguration of the shirt fragment in a way that restored its original appearance but did not stress the textile.

Rauschenberg’s “combines,” created between 1954 and 1964, blur the line between sculpture and painting. Dam, first exhibited at Leo Castelli Gallery in 1959, was created six years earlier than Fossil, and its materials differ somewhat. The work consists of commercial and oil paint, cuts of various textiles—including an entire pants pocket—torn poster signage, printed reproductions of images sourced from contemporary and popular publications, and a small metal object. These materials are layered on top of bare canvas, which is exposed in some areas. Dam falls more on the side of two-dimensional collage, yet its bold composition and subtle embedding of found objects continue to entice viewer interaction. The cumulative effect of touching the work, as well as the accumulated dust and grime that has settled on its surface over time, will be addressed through conservation treatment and will be shared periodically on this page and through social media.

Funding for the conservation of Robert Rauschenberg’s Fossil for Bob Morris (1965) and Dam (1959) was generously provided through a grant from the Bank of America Art Conservation Project.